Last spring, I posted about my version of a modified age-bias plot. One reader commented on that post via Twitter – “Now that you solved the age-bias plot, how about the ‘best’ display of back-calculated length-at-age data, with VonB growth curve overlay?”. In addition, I recently received a question related to the non-convergence of a hierarchical (mixed) model applied to fitting a von Bertalanffy growth function (VBGF) to back-calculated lengths at age. In exploring that question, I realized that a “good” plot of back-calculated lengths at age was needed to understand why the VBGF may (or may not) fit.

Here I write about my initial attempts to visualize back-calculated lengths at age with what are basically spaghetti plots. Spaghetti plots show individual longitudinal traces for each subject (e.g., one example). Recently “spaghetti plots” were in the news to show modeled paths of hurricanes (e.g., I particularly enjoyed this critique).

Data Explanation

In this post, I examine back-calculated lengths (mm) at age for Walleye (Sander vitreus) captured from Lake Mille Lacs, Minnesota in late fall (September-October). [More details are here.] These data were kindly provided by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, are available in the FSAData package, and were used extensively in the “Growth Estimation: Growth Models and Statistical Inference” chapter of the forthcoming “Age and Growth of Fishes: Principles and Techniques” book to be published by the American Fisheries Society. For simplicity of presentation here, these data were reduced to a single year and sex and several superfluous variables were removed. A “snapshot” of the data file is below.

ID Est.Age TL BC.Age BC.Len

2002.10416.F 1 232 1 81.21

2002.10493.F 1 248 1 114.60

2002.10606.F 1 287 1 112.21

2002.1153.F 1 273 1 116.29

2002.1154.F 1 244 1 157.55

2002.20742.F 10 592 6 523.52

2002.20742.F 10 592 7 539.77

2002.20742.F 10 592 8 554.83

2002.20742.F 10 592 9 567.56

2002.20742.F 10 592 10 576.20These fish were captured in late fall such that the observed length includes current year’s growth. However, the observed age does not account for time since the fish’s “birthday.” In other words, the observed age at capture should be a “fractional age” such that it represents completed years of growth plus the fraction of the current year’s growth season completed (i.e., the “current age” should be something like 10.9 rather than 10). An example of this is seen by comparing the observed length at capture (in TL) and the back-calculated length (in BC.Len) to age-1 for the first fish in the data.frame (first line in data shown above).

Some of the plots below require a data.frame where the length and age for the oldest age match in time. In other words, this data.frame should contain the length of the fish on the fish’s last “birthday.” With these data, that length is the back-calculated length at the age (in BC.Age) that matches the age of the fish at the time of capture (in Est.Age). With other data, that length may simply be the length of the fish at the time of capture. An example of this data.frame is below (especially compare the last five lines below to the last five lines in the previous data.frame snippet above).

ID Est.Age TL BC.Age BC.Len

2002.10416.F 1 232 1 81.21

2002.10493.F 1 248 1 114.60

2002.10606.F 1 287 1 112.21

2002.1153.F 1 273 1 116.29

2002.1154.F 1 244 1 157.55

2002.20381.F 10 568 10 563.73

2002.20483.F 10 594 10 580.81

2002.20511.F 10 628 10 618.89

2002.20688.F 10 620 10 611.08

2002.20742.F 10 592 10 576.20Finally, in some of the plots below I include the mean back-calculated length at age. An example of this data.frame is below.

fEst.Age BC.Age mnBC.Len

1 1 111.3464

2 1 113.4633

2 2 225.3060

3 1 98.5338

3 2 211.4096

10 6 505.5437

10 7 538.0147

10 8 558.6757

10 9 571.4900

10 10 579.8577Plots for Exploratory Data Analysis

When modeling fish growth, I explore the data to make observations about (i) variability in length at each age and (ii) “shape” of growth (i.e., whether or not there is evidence for an horizontal asympote or inflection point). When using repeated-measures data, for example from back-calculated lengths at age, I observe the “shape” of growth for each individual and (iii) identify how the back-calculated lengths at age from older fish compare to the back-calculated lengths at age from younger fish (as major differences could suggest “Lee’s Phenomenon”, substantial changes in growth between year-class or over time, or problems with the back-calculation model). In this section, I describe two plots (with some augmentations to the first type) that could be useful during this exploratory stage. In the last section, I describe a plot that could be used for publication.

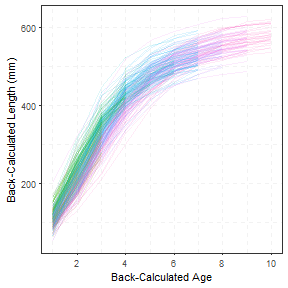

Figure 1 shows longitudinal traces of back-calculated lengths at age for each fish, with separate colors for fish with different observed ages at capture. From this I see variability of approximately 100 mm at each age, individual fish that generally follow the typical shape of a VBGF, and some evidence that back-calculated lengths at earlier ages from “older” fish at capture are somewhat lower than the back-calculated lengths at earlier ages for “younger” fish at capture (this is most evident with the pinkish lines).

Figure 1: Traces of back-calculated lengths at age for each fish. Traces with the same color are fish with the same observed age at capture.

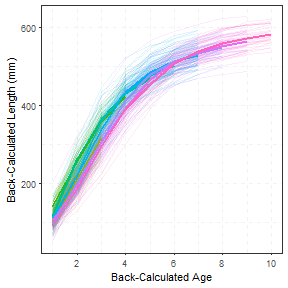

Figure 2 is the same as Figure 1 except that heavy lines have been added for the mean back-calculated lengths at age for fish from each age at capture (Figure 2). Here the evidence that back-calculated lengths at earlier ages from “older” fish at capture are somewhat lower than the back-calculated lengths at earlier ages for “younger” fish at capture is a little more obvious.

Figure 2: Traces of back-calculated lengths at age for each fish with mean back-calculated lengths at age shown by the heavier lines. Traces with the same color are fish with the same observed age at capture.

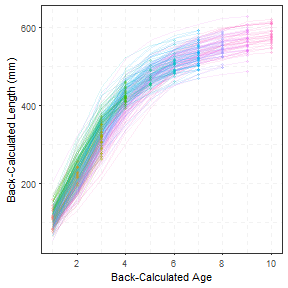

Figure 3 is the same as Figure 1 but also has points for the length and age of each fish at the last completed year of growth. These points are most near to the observed lengths and ages at capture (and will be the observed lengths and ages at capture for datasets where the fish were captured prior to when the current season’s growth had commenced) and, thus, most nearly represent the data that would be used fit a growth model if back-calculations had not been made. With this I observe that most traces of back-calculated lengths at age pass near these points, which suggests that “growth” has not changed dramatically over the time represented in these data and that the model used to back-calculate lengths and ages is not dramatically incorrect.

Figure 3: Traces of back-calculated lengths at age for each fish. Traces with the same color are fish with the same observed age at capture.

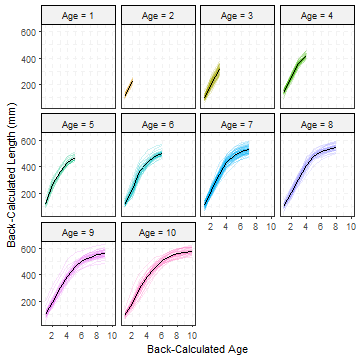

The previous spaghetti plots are cluttered because of the number of individual fish. This clutter can be somewhat reduced by creating separate spaghetti plots for each observed age at capture (Figure 4). From this, I observe the clear start of an asymptote at about age 5, an indication of a slight inflection around age 2(most evident for fish that were older at capture), and that a good portion of the variability in length at early ages may be attributable to fish from different year-classes (i.e., of different observed ages at capture). It is, however, more difficult to see that back-calculated lengths at earlier ages from “older” fish at capture are somewhat lower than the back-calculated lengths at earlier ages for “younger” fish at capture. [Note that I left the facet for age-1 fish in this plot to remind me that there were age-1 fish in these data, even though they do not show a trace. Also, the color here is superfluous and could be removed. I left the color here for comparison with previous figures.]

Figure 4: Traces of back-calculated lengths at age for each fish separated by observed age at capture. Black lines in each facet are the mean back-calculated lengths at age for fish shown in that facet.

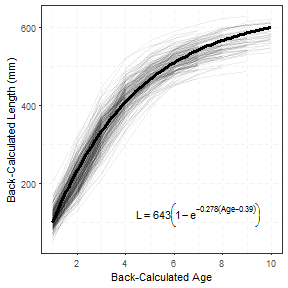

Publication Graphic with Model Overlaid

For publication I would include traces for individual fish, but without color-coding by estimated age at capture, and overlay the population-average growth model (i.e., the growth model expressed from using the “fixed effects” for each model parameter; Figure 5).

Figure 5: Traces of back-calculated lengths at age for each fish (lighter black lines) with the population-averaged von Bertalanffy growth function (dark black line) overlaid. The equation for the best-fit von Bertalanffy growth function is shown.

R Code

## Required packages

library(FSA) # for filterD(), headtail()

library(FSAdata) # for WalleyeML

library(dplyr) # for %>%, select(), arrange(), unique(), group_by, et al.

library(magrittr) # for %<>%

library(ggplot2) # for all of the plotting functions

library(nlme) # for nlme()

## Custom ggplot2 theme ... the black-and-white theme with slightly

## lighter and dashed grid lines and slightly lighter facet labels.

theme_BC <- function() {

theme_bw() %+replace%

theme(

panel.grid.major=element_line(color="gray95",linetype="dashed"),

panel.grid.minor=element_line(color="gray95",linetype="dashed"),

strip.background=element_rect(fill="gray95")

)

}

## Base ggplot

## Uses main data.frame, BC.Age on x- and BC.Len on y-axis

## group=ID to connect lengths at age for each fish

## Applied custom them, labelled axis, controlled ticks on x-axis

## Removed legends ("guides") related to colors and sizes

p <- ggplot(data=df,aes(x=BC.Age,y=BC.Len,group=ID)) +

theme_BC() +

scale_x_continuous("Back-Calculated Age",breaks=seq(0,10,2)) +

scale_y_continuous("Back-Calculated Length (mm)") +

guides(color=FALSE,size=FALSE)

## Main spaghetti plot

p + geom_line(aes(color=fEst.Age),alpha=1/8)

## Spaghetti plot augmented with mean back-calcd lengths at age

p + geom_line(aes(color=fEst.Age),alpha=1/8) +

geom_line(data=df3,aes(x=BC.Age,y=mnBC.Len,group=fEst.Age,color=fEst.Age),size=1)

## Spaghetti plot augmented with last full length at age points

p + geom_line(aes(color=fEst.Age),alpha=1/8) +

geom_point(data=df2,aes(color=fEst.Age),alpha=1/5,size=0.9)

## Make facet labels for the plot below

lbls <- paste("Age =",levels(df$fEst.Age))

names(lbls) <- levels(df$fEst.Age)

## Spaghetti plot separated by age at capture (with means)

p + geom_line(aes(color=fEst.Age),alpha=1/5) +

facet_wrap(~fEst.Age,labeller=labeller(fEst.Age=lbls)) +

geom_line(data=df3,aes(x=BC.Age,y=mnBC.Len,group=NULL),color="black")

## von B equation for the plot

( tmp <- fixef(fitVB) )

lbl <- paste("L==",round(exp(tmp[1]),0),

"*bgroup('(',1-e^-",round(tmp[2],3),

"(Age-",round(tmp[3],2),"),')')")

## Base ggplot

## Uses main data.frame, BC.Age on x- and BC.Len on y-axis

## group=ID to connect lengths at age for each fish

## Applied custom them, labelled axis, controlled ticks on x-axis

## Removed legends ("guides") related to colors and sizes

p <- ggplot(data=df,aes(x=BC.Age,y=BC.Len,group=ID)) +

theme_BC() +

scale_x_continuous("Back-Calculated Age",breaks=seq(0,10,2)) +

scale_y_continuous("Back-Calculated Length (mm)") +

guides(color=FALSE,size=FALSE)

## Add transparent traces for each individual fish

## Add a trace for the overall von B model (in fixed effects)

## Add a label for the overall von B model

p + geom_line(aes(),alpha=1/15) +

stat_function(data=data.frame(T=seq(1,10,0.1)),aes(x=T,y=NULL,group=NULL),

fun=vbT,args=list(logLinf=fixef(fitVB)),size=1.1) +

geom_text(data=data.frame(x=7,y=120),aes(x=x,y=y,group=NULL,

label=lbl),parse=TRUE,size=4)